Shopping centres: Difference between revisions

Cabejskova (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Heart of Europe Stifling Under Concrete:The construction boom of shopping centres in Prague''' | |||

== Foreword == | == Foreword == | ||

The Shopping Gallery Harfa opened in November 2010. The Fenix Shopping Gallery opened in 2008. They both lie at a driving distance of approximately 5 minutes from the biggest shopping area in Prague and the Czech Republic - OC Letňany built in 1999. I visited Fenix on 23 December 2010 and it felt like a ghost town. And on one of the busiest days of the year! This experience made me wonder, how it is possible that energy and resources are wasted on redundant chapels of consumption. In the Czech Republic the so-called area standard – square metres of shopping space per inhabitant – has tripled since 1989 from 0.331<ref>Ministry of Industry and Trade</ref> to 1.1 in 2009<ref>Incoma Research</ref>. That means that every citizen in this country has their own square metre for shopping. Of this, shopping centres represent 0.26 m<sup>2</sup> per inhabitant(sq/inh)<ref name=Ellis>CB Richard Ellis, 2010: http://www.cbre.cz/propertyinfomap/emea/_PDF/EMEA_FPR_CZECH_RETAIL%20_H1_2010_ENG.pdf</ref>. Compared to Liberec for example, which has a value of 1.4 m<sup>2</sup>/inh<ref name=Ellis/>, Prague might seem quite empty with its 0.72<ref name=Ellis/>. The frequency of new shopping centre openings, however, challenges common sense. Prague is fancied for its intimacy and was honoured by becoming a part of the UNESCO world heritage site in 1992 thanks to its historical value. The construction boom is sometimes acused of threatening the town´s uniqueness. Sýkora (2006)<ref name=Sykora>L. Sýkora (2006): Urban Development, Policy and Planning in the Czech Republic and Prague.I'n 'Altrock, Guntner, Huning and Peters: Spatial Planning and Urban Development in the new EU member states. Ashgate Publishing, UK</ref> warns that new investments after 1990 contributed to densification of central city morphology, including rapid growth in car traffic and consequent congestion, which turned out to be especially critical in Prague. Furthermore Sýkora adds that there have been numerous conflicts between investors and those protecting historic buildings and urban landscapes. Another argument in the discussion is environmental sustainability. As the Prague City Development Authority Prague points out, developing commercial areas significantly increases the proportion of built-up land and so opportunities for establishing adequate proportions of greenery decrease. Numerous civic petitions for maintaining parks or other free land in different parts of the city have been signed. | |||

I will take a closer look at the situation with shopping centre construction in Prague and try to establish, what is happening and where the problem lies. | |||

== < | == About shopping centres in general == | ||

Shopping centres have been replacing traditional markets since the last century. They represent the modern lifestyle as they are sometimes called chapels of consumption. I. Smolová<ref name=Smolova>I. Smolová, Z. Szczyrba (2000): Large commercial centers in the Czech Republic - Landscape and regionally aspects of development. Palacky University Olomouc</ref> provides an overall definition: “A Regional Shopping Centre is an architecturally unified complex of commercial facilities planned, constructed, owned and administered as a whole. They represent a concentration of retail stores, catering and services (entertainment and cultural establishments, e.g. multiplex cinemas) aiming to satisfy the customers’ requirements in the field of goods and services in a short-term, mid-term and long-term perspective. The basis of shopping centres is formed by big retail units of the hypermarket type and by specialised superstores (e.g. hobbymarket).” (author’s translation). | |||

The localisation of shopping centres is determined mainly by the proximity of potential customers and accessibility by transport. Given the ratio of sales area to total required area stands at approximately 1:7<ref name=Smolova/>, the localization is limited by the availability of development areas and by lot prices. In relation to Prague, the most sought-after places are on the edges of the city and its high streets. | |||

=== Shopping centres in the Czech Republic with a focus on Prague === | |||

Shopping centres did exist before 1989 – every citizen then knew the famous first western-like Kotva Retail House, for example. Nevertheless the massive expansion of this shopping phenomenon began after the revolution in 1989 as a result of joining the global market. Prague being the capital city forms a kind of bridge between the national and foreign market, and therefore it has been the most affected by globalisation and internationalisation. The service sector has grown rapidly, whereas industry has been left behind which has resulted in the existence of brownfields in several areas. The most visible recent urban tendency is suburbanisation, including outward migration and commercialisation. Stores, logistic centres and shopping areas have been built. As I mentioned in the foreword, the area standard of Prague has the value of 0.72 m<sup>2</sup> per citizen. The total number of shopping centres in the capital is 38, their area represents 33% of the national shopping centre area<ref name=Ellis/>. | |||

[[Image:CBRE SC.jpg]] | |||

'''Fig. 1: Shopping Centre Development in the Czech Republic'''<ref name=Ellis/> | |||

''Figure 1 shows that shopping centres experienced a steep increase in construction in the year 1998. The other peak was in 2008, which is the year of the opening of big Prague shopping centres like Arkády Pankrác (40,000m<sup>2</sup>) or the afore mentioned Fenix Gallery (12 000m<sup>2</sup>). Most of the new construction was located in smaller towns however - the focus of investors moved away from the cities to these less saturated regional towns. <ref>http://www.ct24.cz/ekonomika/12186-boom-nakupnich-center-se-presouva-do-regionu/</ref> The graph shows there has been a decreasing tendency in the last two years. In 2010, the financial crisis was manifested in construction perhaps even more than in others fields, as only one shopping centre opened in Prague(Harfa Gallery). '' | |||

== Legislation == | |||

Three main laws are relevant to the topic of shopping centre construction in the Czech Republic: firstly the Construction Act No.183/2006 Coll.; secondly, Act No.334/1992 Coll., on Protection of Agricultural Soil; and lastly Act No.100/2001 Coll., containing Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). These include the general principles of building procedures, the conditions of use of agricultural soil for other than agricultural purposes and the criteria for EIA (for example, since 2007 projects with less than 3,000 m2 and fewer than 100 parking spaces can be omitted from the EIA). Complex regulations concerning specifically big shopping centres are missing though. | |||

=== Policy and Planning === | |||

In the Czech Republic, the responsibility for policy making rests primarily with municipal governments. The problem is that the so-called functional urban region extends the political boundaries of the core cities. In regard to Prague, it is surrounded by over 170 small municipalities which are economically and legally independent units and whose decision-making process lacks wider coordination. Moreover, the metropolitan area of Prague is governed by two regional entities – Prague itself and Central Bohemia which tend to compete rather than cooperate on the question of joint development. | |||

Prague itself, as a statutory town, has its municipal territory divided into 57 boroughs, therefore establishing a second tier of local government which takes advantage of the gained partial autonomy in decision making. However, they ought to respect two citywide planning documents – The Master Plan and The Strategic Plan. The former is a physical plan that specifies the special arrangements and land use in the medium term, while the latter specifies the long term priorities of socio-economic development. | |||

The Strategic Plan specifies controlled development and coordinated management and decision-making in order to achieve prosperity, a healthy and cultural environment, and the preservation of values which make Prague one of the most beautiful cities in the world. It is an agreement between politicians, specialists, corporate sector representatives and inhabitants. One of the five pillars focuses on the quality of the environment: “Prague endeavours to achieve a high quality of both natural and urban development, while observing the principles of sustainability. It wants to substantially reduce pollution in the city and create balance between human settlement and landscape in order to become a clean, healthy and harmonious city<ref name="Sykora" />.” Besides these two documents, Prague has worked on policies in accordance with EU demands and has created a Regional Development Strategy which basically matches the Strategic Plan. | |||

=== A feedback on the current policy === | |||

''In this part, the resume of a feedback document - Planning Analytical Materials <ref>http://www.urm.cz/uploads/assets/soubory/data/UAP/UAP_book/kapitoly/04_kapitola_4_uap_2008.pdf</ref>- carried out by the City Development Authority Prague in 2008 is provided:'' | |||

The | The ongoing pressure on building new shopping centres and office complexes is seen as a threat to the lively metropolitan structure and to the transport network. The new European trend is to mix compact construction with lower capacity facilities. The newly constructed and reconstructed big capacities of retail outlets and offices, such as the newly opened Palladium complex, place emphasis on traffic because of parking demands and with their 100% built-up land they limit areas for new parks or greenery for the relaxation of local inhabitants and workers. Due to greater interest in shopping complexes the survival of existing parks in the Prague city centre is endangered as well. | ||

A negative trend is the low support of the private sector in meeting the financially less attractive functions of the city, which includes public facilities, greenery and recreation areas. There is also a mismatch between customer interest in traditional dispersed retail networks and the new fashion for travelling to big shopping centres on the outskirts of Prague which generates traffic congestion and so causes damage to the environment. | |||

A | A problem solvable by the Master Plan is insufficient coordination of store and logistic areas in the city surroundings. What is beyond the competence of the plan, however, is regulation of the retail network in favour of smaller units, as well as the pressure of economic land use at the expense of urban aspects and environmental protection. | ||

The Planning Analytical | The Planning Analytical Materials of 2008 recommend that no more land is dedicated to big shopping centres except for newly proposed district centres. | ||

== | == Problems connected to commercialisation – urban, environmental and social aspects == | ||

The existence of shopping centres definitely brings several benefits to society. These can be employment, shopping availability, economic growth. However, numerous unpleasant consequences of the construction of shopping centres have been observed. A list of the most important ones follows. | |||

The | <u>1. The question of population decline in the city centre emerges as more and more buildings are loosing their residential function and are used for office or retail areas instead. </u><br> | ||

<u>2. As a result, people move out of the centre but commute there to work or for shopping, which causes traffic congestion. Suppliers contribute to this congestion as well. </u> | |||

<br> | |||

== | {| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" width="300" | ||

|- | |||

! scope="col" | traffic increase | |||

! scope="col" | number of retail units | |||

! scope="col" | rate of retail units | |||

|- | |||

| < 5% | |||

| 66 | |||

| 26.50 % | |||

|- | |||

| 5.00-9,99% | |||

| 67 | |||

| 26.90 % | |||

|- | |||

| 10-19,99 % | |||

| 65 | |||

| 26.10 % | |||

|- | |||

| 20-29.99 % | |||

| 28 | |||

| 11.20 % | |||

|- | |||

| > 30% | |||

| 23 | |||

| 9.20 % | |||

|- | |||

| total | |||

| 249 | |||

| 100 % | |||

|- | |||

| average | |||

| <br> | |||

| 11 % | |||

|} | |||

'''Fig. 2: The impact of retail construction on traffic, NESEHNUTÍ''' <ref name="nesehnuti">NGO NESEHNUTÍ http://nesehnuti.cz/publikace/vyzkum_2003-2009.pdf</ref> | |||

The | *''This chart shows the proportion of retail units by the percentage of traffic increase that appeared after the opening. The conclusion is that 1/4 of the cases caused an increase of 5% maximum. On the other hand, the same number of cases reported an increase of up to 20%, which might be horrific for infrastructure in cases where it was often congested already. Increased traffic is a burden not only for air quality, but also worsens noise pollution (currently one of the worst problems of the Czech environment) and affects pedestrian comfort and safety, too. '' | ||

<u>3. New construction investments are being made at the expense of diminishing greenery that is already rare in the city centre. </u> | |||

[[Image:Envis vlastni.jpg]] | |||

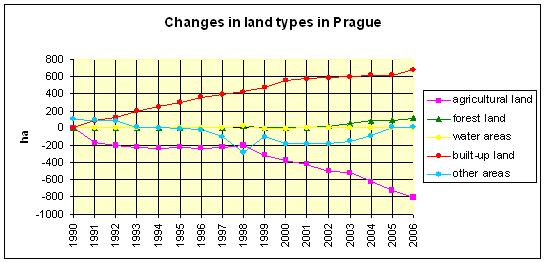

'''Fig. 3: The development of different types of land in Prague, ENVIS'''<ref>ENVIS, 2007: [http://envis.praha-mesto.cz/%28cvvouk454exf1gmszo5zjmia%29/zdroj.aspx?typ=2&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;Id=79433&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;sh=-1015397439 available on-line]</ref> | |||

''Even though politicians like to pride themselves on the numbers of newly planted trees or hectares of newly established urban greenery, this chart shows that in total natural land (forest, water, agricultural and other areas) has more or less stagnated, whereas the built-up area has increased significantly since 1990.'' | |||

<u>4. Construction of suburban shopping centres occupies even more land, because roads and parking lots have to be built too. Traffic increases again. Research from EIA 2003-2009<ref name="nesehnuti" /> shows that</u> | |||

<br> | |||

*72% of shopping centres in the Czech Republic have been built in the suburbs | |||

*Buildings take up 30% of the construction lot, roads and parking lots 45% | |||

*92% of parking areas have been designed as surface types, the rest as underground or internal | |||

*One half of shopping centres have been built upon green fields, 10% of that land being firsty category agricultural soil intended to be built upon only in the most special cases. | |||

*46% of shopping centres have had a negative effect on the landscape (soil degradation, tree cutting, endangering ecological stability etc) | |||

<u>5. Small, traditional retailers are threatened and see shopping centres as “unfair rivals”.</u> | |||

<u>6. The design of new shopping centres often omits local urban patterns and so interrupts the landscape or even historical values. A study<ref>J. Temelová (2004): The Reflection of Globalization in non-housing estate in Prague after 1990. In M.Ouředníček: Social Goegraphy of the Prague Region. Charles University in Prague, 2006</ref> on this topic claims these factors:</u> | |||

* A trend towards globally active artists creating international images of cities has emerged and buildings are designed to show global success as a part of the marketing strategy of their owners. This means that the architecture is becoming rather unified, local specific customs are often omitted and so one can observe the same designs worldwide. Example images, both from abroad and Prague are shown to prove the theory: | |||

[[Image:240px-Downtown of Rio de Janeiro.jpg]] Rio De Janeiro, Brazil | |||

[[Image:240px-Toronto.jpg]]Toronto, Canada | |||

[[Image:240px-Praha Pankrac mrakodrapy.jpg]]Praha Pankrác, Czech Republic | |||

[[Image:240px-Villagecinemas cernymost.jpg]]Entertainment centre Černý Most, Prague, Czech Republic | |||

*New projects engage foreign investors, which is reflected in their names (Anděl Bussiness Center), in the similarity of financing (the developer designs the exterior whereas the interior composition is chosen by the client) and in construction similarity. A new type of construction occurs, it is the so-called groundscraper model. A groundscraper takes the american way (skyscraper) of construction but adjusts it to European conditions. It is a horizontal building fulfiling a whole block and besides offices it includes other functions - shopping, entertainment, food. The concept can be illustrated by these pictures: | |||

[[Image:240px-AON WAKAMATSU SHOPPING CENTER.jpg]] Shopping centre Wakamatsu. Fukuoka, Japan | |||

[[Image:240px-Galerie Butovice.jpg]] Galerie Butovice, Prague, Czech Republic | |||

[[Image:240px-Praha-letnany.jpg]] Shopping centre Letňany, Prague, Czech Republic | |||

[[Image:240px-Praha Chodov Centrum Chodov a okoli.jpg]]Centrum Chodov, Prague, Czech Republic | |||

*Suburban stores and shopping centres in particular express the rationality and purpose of machines of mass consumption and create the atmosphere of a placeless city | |||

<br> | |||

== Conflict == | |||

Civil society NGOs were probably the first to start complaining about retail construction as it has affected the direct surrounding of people’s homes. A good example is an NGO called Healthy Life founded in 1998 in the municipal district of Prague 10 in order to protest against the construction of Nákupní centrum EDEN (EDEN Shopping Centre), located close to the Slavia football ground. As the NGO’s website<ref>[http://nno.ecn.cz/index.stm?apc=nP2z1-161309&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nocache=invalidate&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;sh_itm=d8f9c3fa1af9670e34fc21399469e5e6&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;add_disc=1&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;parent_id=2d04b53480894ea9832979b7bfb6972f available at Econet web]</ref> claims, this shopping centre was built despite the lack of necessary consent. This NGO and other bodies appealed against the Prague 10 council´s permission for the construction and even though the Supreme Court decided that the decision-making process had been wrong and must start again (and so the building permit was invalid), the investors started cutting trees and building an engineering network. Later on there was not enough power on the part of the opponents to stop the construction. | |||

The most important arguments of Healthy Life were that the park, which lay on the building allotment was the only green land in a wide area and that the construction of a shopping centre would increase traffic and exacerbate air-pollution. | |||

[[Image:240pxEden Shopping Development - geograph.org.uk - 255613.jpg]]The development of Eden Shopping Centre, Prague, Czech Republic | |||

[[Image:240px-Tesco headquarters Czech .jpg]]Eden shopping centre, Prague, Czech republic | |||

Another example is the Pankrácké Pláně (Pankrác Plain) with ArkádyPankrác (a shopping centre), an area where skyscrapers have been built and a big discussion ensues about the threat of UNESCO punishment (because the skyscrapers might disrupt the city’s panorama). Again an NGO was founded and the dispute went on. Inhabitants always refer to the EIA process because it is their only legal option for joining in the discussion. They hope the EIA results might cause serious trouble for the investor, but all the previous cases show that this political/environmental instrument is not powerful enough to actually stop a whole project. | |||

The media have supported the fragmented civil societyefforts every now and then. Articles with these headlines, for example, have been published: “A stamp is enough to turn a park into a parking lot” (Ekonom, 9.1.2003) or “Arkády Pankrác is opening, other shopping centres struggle to survive”(ČT 24, 14.11.2008) or “Shopping centres are mounting up despite the crisis” (Profit.cz, 27.4.2009). | |||

Politicians, important actors in the conflict, usually remain rather silent and not many explanations or quotations from them can be found. From the few comments made in the media I have assumed that their argumentation in favour of shopping centre construction is of a financial character, that is to say that the given district wants to profit from selling allotments and claims shopping centres are of local importance and raise the economic value of the area. | |||

As for the developers, their role is quite simple – they act as businessmen looking for profit and don’t pay much attention to other aspects. | |||

== Future development == | |||

The structure of Czech retailing has undergone a rapid evolution since 1989. The construction of new shops and commercial centres has been so massive that it has created an image of uncontrolled sprawl. The numbers say we have recently reached the European average level as concerns the area standard (square metres of shopping space per inhabitant), which undermines the worries of environmentalists – there is probably no over-construction if it’s the same as in the rest of Europe! Examples show, however, that the development dictated by investors without much planning restrictions from the higher political level has not always been successful. That means that over-construction has occurred and it has been reflected in lower incomes for investors, some shopping centres are even half-empty<ref>http://ekonomika.idnes.cz/prvni-nakupni-centrum-propadlo-bance-galerie-butovice-se-vratila-ing-1j4-/ekonomika.aspx?c=A100722_193302_ekonomika_vel</ref> and their owners struggle to come up with new marketing ideas such as turning the parking areas into paintball fields in order to attract back customers. <ref>http://ekonomika.idnes.cz/obchodnich-center-je-moc-hure-dostupna-skomiraji-f64-/ekonomika.aspx?c=A080727_211240_ekonomika_abr</ref><br> | |||

To conclude I will cite an up-to-date article from Lidové noviny (11.1.2011). Its headline is “The twilight of huge shopping centres” and points out that in 2011 no shopping centres will be opened (for the first time since 1990!) because the Czech Republic is saturated. This fact is a result of market self-regulation rather than urban and political planning, but it seems that the construction boom in shopping centres has hopefully ended together with the first decade of the millennium and therefore the future development should be pretty much calmer and slower. Current trends are toward to the establishment of retail in existing buildings (eg.high streets) instead of constructing massive complexes on green fields. | |||

== Rising challenges == | |||

During the development of my case study I learned that the construction of shopping centres features more aspects than the ecological one I had been anxious about. Architects are concerned about design, small traders feel discriminated against, residents complain about traffic congestion… | |||

The most worrying matter, however, is the lack of effective communication in the process preceding the construction itself. Starting with insufficient cooperation between administrative bodies through to the absence of specialist tuition (architects, environmentalists) and ending with limited options for participation by residents. | |||

We face a number of challenges in this topic: Are the laws concerning the decision making process respected in the Czech Republic?; Do numerous shopping centres present a desirable way of development for the majority of people or is it only that the pressures of investors are stronger in the questions of land use? Do we apply enough control mechanisms to prevent corruption and ensure equal possibilities for the involvement of all affected parties? | |||

== References == | |||

<references /> | |||

{{License cc|Zuzana Cabejšková}} | |||

[[Category:Case studies]] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:18, 30 August 2017

Heart of Europe Stifling Under Concrete:The construction boom of shopping centres in Prague

Foreword

The Shopping Gallery Harfa opened in November 2010. The Fenix Shopping Gallery opened in 2008. They both lie at a driving distance of approximately 5 minutes from the biggest shopping area in Prague and the Czech Republic - OC Letňany built in 1999. I visited Fenix on 23 December 2010 and it felt like a ghost town. And on one of the busiest days of the year! This experience made me wonder, how it is possible that energy and resources are wasted on redundant chapels of consumption. In the Czech Republic the so-called area standard – square metres of shopping space per inhabitant – has tripled since 1989 from 0.331[1] to 1.1 in 2009[2]. That means that every citizen in this country has their own square metre for shopping. Of this, shopping centres represent 0.26 m2 per inhabitant(sq/inh)[3]. Compared to Liberec for example, which has a value of 1.4 m2/inh[3], Prague might seem quite empty with its 0.72[3]. The frequency of new shopping centre openings, however, challenges common sense. Prague is fancied for its intimacy and was honoured by becoming a part of the UNESCO world heritage site in 1992 thanks to its historical value. The construction boom is sometimes acused of threatening the town´s uniqueness. Sýkora (2006)[4] warns that new investments after 1990 contributed to densification of central city morphology, including rapid growth in car traffic and consequent congestion, which turned out to be especially critical in Prague. Furthermore Sýkora adds that there have been numerous conflicts between investors and those protecting historic buildings and urban landscapes. Another argument in the discussion is environmental sustainability. As the Prague City Development Authority Prague points out, developing commercial areas significantly increases the proportion of built-up land and so opportunities for establishing adequate proportions of greenery decrease. Numerous civic petitions for maintaining parks or other free land in different parts of the city have been signed.

I will take a closer look at the situation with shopping centre construction in Prague and try to establish, what is happening and where the problem lies.

About shopping centres in general

Shopping centres have been replacing traditional markets since the last century. They represent the modern lifestyle as they are sometimes called chapels of consumption. I. Smolová[5] provides an overall definition: “A Regional Shopping Centre is an architecturally unified complex of commercial facilities planned, constructed, owned and administered as a whole. They represent a concentration of retail stores, catering and services (entertainment and cultural establishments, e.g. multiplex cinemas) aiming to satisfy the customers’ requirements in the field of goods and services in a short-term, mid-term and long-term perspective. The basis of shopping centres is formed by big retail units of the hypermarket type and by specialised superstores (e.g. hobbymarket).” (author’s translation).

The localisation of shopping centres is determined mainly by the proximity of potential customers and accessibility by transport. Given the ratio of sales area to total required area stands at approximately 1:7[5], the localization is limited by the availability of development areas and by lot prices. In relation to Prague, the most sought-after places are on the edges of the city and its high streets.

Shopping centres in the Czech Republic with a focus on Prague

Shopping centres did exist before 1989 – every citizen then knew the famous first western-like Kotva Retail House, for example. Nevertheless the massive expansion of this shopping phenomenon began after the revolution in 1989 as a result of joining the global market. Prague being the capital city forms a kind of bridge between the national and foreign market, and therefore it has been the most affected by globalisation and internationalisation. The service sector has grown rapidly, whereas industry has been left behind which has resulted in the existence of brownfields in several areas. The most visible recent urban tendency is suburbanisation, including outward migration and commercialisation. Stores, logistic centres and shopping areas have been built. As I mentioned in the foreword, the area standard of Prague has the value of 0.72 m2 per citizen. The total number of shopping centres in the capital is 38, their area represents 33% of the national shopping centre area[3].

Fig. 1: Shopping Centre Development in the Czech Republic[3]

Figure 1 shows that shopping centres experienced a steep increase in construction in the year 1998. The other peak was in 2008, which is the year of the opening of big Prague shopping centres like Arkády Pankrác (40,000m2) or the afore mentioned Fenix Gallery (12 000m2). Most of the new construction was located in smaller towns however - the focus of investors moved away from the cities to these less saturated regional towns. [6] The graph shows there has been a decreasing tendency in the last two years. In 2010, the financial crisis was manifested in construction perhaps even more than in others fields, as only one shopping centre opened in Prague(Harfa Gallery).

Legislation

Three main laws are relevant to the topic of shopping centre construction in the Czech Republic: firstly the Construction Act No.183/2006 Coll.; secondly, Act No.334/1992 Coll., on Protection of Agricultural Soil; and lastly Act No.100/2001 Coll., containing Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). These include the general principles of building procedures, the conditions of use of agricultural soil for other than agricultural purposes and the criteria for EIA (for example, since 2007 projects with less than 3,000 m2 and fewer than 100 parking spaces can be omitted from the EIA). Complex regulations concerning specifically big shopping centres are missing though.

Policy and Planning

In the Czech Republic, the responsibility for policy making rests primarily with municipal governments. The problem is that the so-called functional urban region extends the political boundaries of the core cities. In regard to Prague, it is surrounded by over 170 small municipalities which are economically and legally independent units and whose decision-making process lacks wider coordination. Moreover, the metropolitan area of Prague is governed by two regional entities – Prague itself and Central Bohemia which tend to compete rather than cooperate on the question of joint development.

Prague itself, as a statutory town, has its municipal territory divided into 57 boroughs, therefore establishing a second tier of local government which takes advantage of the gained partial autonomy in decision making. However, they ought to respect two citywide planning documents – The Master Plan and The Strategic Plan. The former is a physical plan that specifies the special arrangements and land use in the medium term, while the latter specifies the long term priorities of socio-economic development.

The Strategic Plan specifies controlled development and coordinated management and decision-making in order to achieve prosperity, a healthy and cultural environment, and the preservation of values which make Prague one of the most beautiful cities in the world. It is an agreement between politicians, specialists, corporate sector representatives and inhabitants. One of the five pillars focuses on the quality of the environment: “Prague endeavours to achieve a high quality of both natural and urban development, while observing the principles of sustainability. It wants to substantially reduce pollution in the city and create balance between human settlement and landscape in order to become a clean, healthy and harmonious city[4].” Besides these two documents, Prague has worked on policies in accordance with EU demands and has created a Regional Development Strategy which basically matches the Strategic Plan.

A feedback on the current policy

In this part, the resume of a feedback document - Planning Analytical Materials [7]- carried out by the City Development Authority Prague in 2008 is provided:

The ongoing pressure on building new shopping centres and office complexes is seen as a threat to the lively metropolitan structure and to the transport network. The new European trend is to mix compact construction with lower capacity facilities. The newly constructed and reconstructed big capacities of retail outlets and offices, such as the newly opened Palladium complex, place emphasis on traffic because of parking demands and with their 100% built-up land they limit areas for new parks or greenery for the relaxation of local inhabitants and workers. Due to greater interest in shopping complexes the survival of existing parks in the Prague city centre is endangered as well.

A negative trend is the low support of the private sector in meeting the financially less attractive functions of the city, which includes public facilities, greenery and recreation areas. There is also a mismatch between customer interest in traditional dispersed retail networks and the new fashion for travelling to big shopping centres on the outskirts of Prague which generates traffic congestion and so causes damage to the environment.

A problem solvable by the Master Plan is insufficient coordination of store and logistic areas in the city surroundings. What is beyond the competence of the plan, however, is regulation of the retail network in favour of smaller units, as well as the pressure of economic land use at the expense of urban aspects and environmental protection.

The Planning Analytical Materials of 2008 recommend that no more land is dedicated to big shopping centres except for newly proposed district centres.

Problems connected to commercialisation – urban, environmental and social aspects

The existence of shopping centres definitely brings several benefits to society. These can be employment, shopping availability, economic growth. However, numerous unpleasant consequences of the construction of shopping centres have been observed. A list of the most important ones follows.

1. The question of population decline in the city centre emerges as more and more buildings are loosing their residential function and are used for office or retail areas instead.

2. As a result, people move out of the centre but commute there to work or for shopping, which causes traffic congestion. Suppliers contribute to this congestion as well.

| traffic increase | number of retail units | rate of retail units |

|---|---|---|

| < 5% | 66 | 26.50 % |

| 5.00-9,99% | 67 | 26.90 % |

| 10-19,99 % | 65 | 26.10 % |

| 20-29.99 % | 28 | 11.20 % |

| > 30% | 23 | 9.20 % |

| total | 249 | 100 % |

| average | 11 % |

Fig. 2: The impact of retail construction on traffic, NESEHNUTÍ [8]

- This chart shows the proportion of retail units by the percentage of traffic increase that appeared after the opening. The conclusion is that 1/4 of the cases caused an increase of 5% maximum. On the other hand, the same number of cases reported an increase of up to 20%, which might be horrific for infrastructure in cases where it was often congested already. Increased traffic is a burden not only for air quality, but also worsens noise pollution (currently one of the worst problems of the Czech environment) and affects pedestrian comfort and safety, too.

3. New construction investments are being made at the expense of diminishing greenery that is already rare in the city centre.

Fig. 3: The development of different types of land in Prague, ENVIS[9]

Even though politicians like to pride themselves on the numbers of newly planted trees or hectares of newly established urban greenery, this chart shows that in total natural land (forest, water, agricultural and other areas) has more or less stagnated, whereas the built-up area has increased significantly since 1990.

4. Construction of suburban shopping centres occupies even more land, because roads and parking lots have to be built too. Traffic increases again. Research from EIA 2003-2009[8] shows that

- 72% of shopping centres in the Czech Republic have been built in the suburbs

- Buildings take up 30% of the construction lot, roads and parking lots 45%

- 92% of parking areas have been designed as surface types, the rest as underground or internal

- One half of shopping centres have been built upon green fields, 10% of that land being firsty category agricultural soil intended to be built upon only in the most special cases.

- 46% of shopping centres have had a negative effect on the landscape (soil degradation, tree cutting, endangering ecological stability etc)

5. Small, traditional retailers are threatened and see shopping centres as “unfair rivals”.

6. The design of new shopping centres often omits local urban patterns and so interrupts the landscape or even historical values. A study[10] on this topic claims these factors:

- A trend towards globally active artists creating international images of cities has emerged and buildings are designed to show global success as a part of the marketing strategy of their owners. This means that the architecture is becoming rather unified, local specific customs are often omitted and so one can observe the same designs worldwide. Example images, both from abroad and Prague are shown to prove the theory:

Entertainment centre Černý Most, Prague, Czech Republic

Entertainment centre Černý Most, Prague, Czech Republic

- New projects engage foreign investors, which is reflected in their names (Anděl Bussiness Center), in the similarity of financing (the developer designs the exterior whereas the interior composition is chosen by the client) and in construction similarity. A new type of construction occurs, it is the so-called groundscraper model. A groundscraper takes the american way (skyscraper) of construction but adjusts it to European conditions. It is a horizontal building fulfiling a whole block and besides offices it includes other functions - shopping, entertainment, food. The concept can be illustrated by these pictures:

Shopping centre Wakamatsu. Fukuoka, Japan

Shopping centre Wakamatsu. Fukuoka, Japan

Galerie Butovice, Prague, Czech Republic

Galerie Butovice, Prague, Czech Republic

Shopping centre Letňany, Prague, Czech Republic

Shopping centre Letňany, Prague, Czech Republic

Centrum Chodov, Prague, Czech Republic

Centrum Chodov, Prague, Czech Republic

- Suburban stores and shopping centres in particular express the rationality and purpose of machines of mass consumption and create the atmosphere of a placeless city

Conflict

Civil society NGOs were probably the first to start complaining about retail construction as it has affected the direct surrounding of people’s homes. A good example is an NGO called Healthy Life founded in 1998 in the municipal district of Prague 10 in order to protest against the construction of Nákupní centrum EDEN (EDEN Shopping Centre), located close to the Slavia football ground. As the NGO’s website[11] claims, this shopping centre was built despite the lack of necessary consent. This NGO and other bodies appealed against the Prague 10 council´s permission for the construction and even though the Supreme Court decided that the decision-making process had been wrong and must start again (and so the building permit was invalid), the investors started cutting trees and building an engineering network. Later on there was not enough power on the part of the opponents to stop the construction.

The most important arguments of Healthy Life were that the park, which lay on the building allotment was the only green land in a wide area and that the construction of a shopping centre would increase traffic and exacerbate air-pollution.

The development of Eden Shopping Centre, Prague, Czech Republic

The development of Eden Shopping Centre, Prague, Czech Republic

Eden shopping centre, Prague, Czech republic

Eden shopping centre, Prague, Czech republic

Another example is the Pankrácké Pláně (Pankrác Plain) with ArkádyPankrác (a shopping centre), an area where skyscrapers have been built and a big discussion ensues about the threat of UNESCO punishment (because the skyscrapers might disrupt the city’s panorama). Again an NGO was founded and the dispute went on. Inhabitants always refer to the EIA process because it is their only legal option for joining in the discussion. They hope the EIA results might cause serious trouble for the investor, but all the previous cases show that this political/environmental instrument is not powerful enough to actually stop a whole project.

The media have supported the fragmented civil societyefforts every now and then. Articles with these headlines, for example, have been published: “A stamp is enough to turn a park into a parking lot” (Ekonom, 9.1.2003) or “Arkády Pankrác is opening, other shopping centres struggle to survive”(ČT 24, 14.11.2008) or “Shopping centres are mounting up despite the crisis” (Profit.cz, 27.4.2009).

Politicians, important actors in the conflict, usually remain rather silent and not many explanations or quotations from them can be found. From the few comments made in the media I have assumed that their argumentation in favour of shopping centre construction is of a financial character, that is to say that the given district wants to profit from selling allotments and claims shopping centres are of local importance and raise the economic value of the area.

As for the developers, their role is quite simple – they act as businessmen looking for profit and don’t pay much attention to other aspects.

Future development

The structure of Czech retailing has undergone a rapid evolution since 1989. The construction of new shops and commercial centres has been so massive that it has created an image of uncontrolled sprawl. The numbers say we have recently reached the European average level as concerns the area standard (square metres of shopping space per inhabitant), which undermines the worries of environmentalists – there is probably no over-construction if it’s the same as in the rest of Europe! Examples show, however, that the development dictated by investors without much planning restrictions from the higher political level has not always been successful. That means that over-construction has occurred and it has been reflected in lower incomes for investors, some shopping centres are even half-empty[12] and their owners struggle to come up with new marketing ideas such as turning the parking areas into paintball fields in order to attract back customers. [13]

To conclude I will cite an up-to-date article from Lidové noviny (11.1.2011). Its headline is “The twilight of huge shopping centres” and points out that in 2011 no shopping centres will be opened (for the first time since 1990!) because the Czech Republic is saturated. This fact is a result of market self-regulation rather than urban and political planning, but it seems that the construction boom in shopping centres has hopefully ended together with the first decade of the millennium and therefore the future development should be pretty much calmer and slower. Current trends are toward to the establishment of retail in existing buildings (eg.high streets) instead of constructing massive complexes on green fields.

Rising challenges

During the development of my case study I learned that the construction of shopping centres features more aspects than the ecological one I had been anxious about. Architects are concerned about design, small traders feel discriminated against, residents complain about traffic congestion…

The most worrying matter, however, is the lack of effective communication in the process preceding the construction itself. Starting with insufficient cooperation between administrative bodies through to the absence of specialist tuition (architects, environmentalists) and ending with limited options for participation by residents.

We face a number of challenges in this topic: Are the laws concerning the decision making process respected in the Czech Republic?; Do numerous shopping centres present a desirable way of development for the majority of people or is it only that the pressures of investors are stronger in the questions of land use? Do we apply enough control mechanisms to prevent corruption and ensure equal possibilities for the involvement of all affected parties?

References

- ↑ Ministry of Industry and Trade

- ↑ Incoma Research

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 CB Richard Ellis, 2010: http://www.cbre.cz/propertyinfomap/emea/_PDF/EMEA_FPR_CZECH_RETAIL%20_H1_2010_ENG.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 L. Sýkora (2006): Urban Development, Policy and Planning in the Czech Republic and Prague.I'n 'Altrock, Guntner, Huning and Peters: Spatial Planning and Urban Development in the new EU member states. Ashgate Publishing, UK

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 I. Smolová, Z. Szczyrba (2000): Large commercial centers in the Czech Republic - Landscape and regionally aspects of development. Palacky University Olomouc

- ↑ http://www.ct24.cz/ekonomika/12186-boom-nakupnich-center-se-presouva-do-regionu/

- ↑ http://www.urm.cz/uploads/assets/soubory/data/UAP/UAP_book/kapitoly/04_kapitola_4_uap_2008.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 NGO NESEHNUTÍ http://nesehnuti.cz/publikace/vyzkum_2003-2009.pdf

- ↑ ENVIS, 2007: available on-line

- ↑ J. Temelová (2004): The Reflection of Globalization in non-housing estate in Prague after 1990. In M.Ouředníček: Social Goegraphy of the Prague Region. Charles University in Prague, 2006

- ↑ available at Econet web

- ↑ http://ekonomika.idnes.cz/prvni-nakupni-centrum-propadlo-bance-galerie-butovice-se-vratila-ing-1j4-/ekonomika.aspx?c=A100722_193302_ekonomika_vel

- ↑ http://ekonomika.idnes.cz/obchodnich-center-je-moc-hure-dostupna-skomiraji-f64-/ekonomika.aspx?c=A080727_211240_ekonomika_abr

| Author: Zuzana Cabejšková. This article was published under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. How to cite the article: Zuzana Cabejšková. (19. 04. 2024). Shopping centres. VCSEWiki. Retrieved 05:46 19. 04. 2024) from: <https://vcsewiki.czp.cuni.cz/w/index.php?title=Shopping_centres&oldid=5471>. |