“The Low Price” of the textile discounter KiK – consequences for labour conditions in textile factories in Bangladesh: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

The auditor arrives at the factory unannounced and starts his audit by talking to the management and asking for some documents. Then he inspects the whole factory with regard of working conditions, safety aspects and health requirements. He also chooses workers for a later interview. This interview is carried out in absence of the authorities of the factory.<ref name="C" /> “This means that they can find out whether the maximum working hours are adhered to and whether their monthly wages, including overtime, are paid correctly.”<ref name="C" /> After this the auditor evaluates the factory and talks to the management about lacking standards and a suitable procedure to reach the conduct wished state. The audit report is send to the KiK home-office. After a while a re-audit takes place where all criticised points are under examination again. | The auditor arrives at the factory unannounced and starts his audit by talking to the management and asking for some documents. Then he inspects the whole factory with regard of working conditions, safety aspects and health requirements. He also chooses workers for a later interview. This interview is carried out in absence of the authorities of the factory.<ref name="C" /> “This means that they can find out whether the maximum working hours are adhered to and whether their monthly wages, including overtime, are paid correctly.”<ref name="C" /> After this the auditor evaluates the factory and talks to the management about lacking standards and a suitable procedure to reach the conduct wished state. The audit report is send to the KiK home-office. After a while a re-audit takes place where all criticised points are under examination again. | ||

This last paragraph describes the way an audit should be and if it functions this way, it is definitely a good instrument to control the code of conduct. The next chapter is based on a research study in 2008 conducted by the society of “Alternative Movement for resources and Freedom” (AMRF), a Bangladeshi NGO, by order of the “Clean Clothes Campaign”. This study was made to reveal the real working conditions in the factories of the suppliers of KiK and Lidl. A team of researchers interviewed 136 workers in six factories. They answered questionnaires and 31 of them were asked in group discussions.<ref name="A" /> Chapter 4 will present the opposite perspective to the announcement of KiK. It shows how the rules and control-audits are tricked and under which conditions the mostly female workers suffer. | This last paragraph describes the way an audit should be and if it functions this way, it is definitely a good instrument to control the code of conduct. The next chapter is based on a research study in 2008 conducted by the society of “Alternative Movement for resources and Freedom” (AMRF), a Bangladeshi NGO, by order of the “Clean Clothes Campaign”. This study was made to reveal the real working conditions in the factories of the suppliers of KiK and Lidl. A team of researchers interviewed 136 workers in six factories. They answered questionnaires and 31 of them were asked in group discussions.<ref name="A" /> Chapter 4 will present the opposite perspective to the announcement of KiK. It shows how the rules and control-audits are tricked and under which conditions the mostly female workers suffer. | ||

<br> | |||

=== <u>4) Bangladeshi labour standards in supplier-factories of KiK</u><br> === | === <u>4) Bangladeshi labour standards in supplier-factories of KiK</u><br> === | ||

The research study in 2008 revealed that the labour standards at Bangladeshi factories of the suppliers of KiK were very bad. The workers aren’t allowed to build up or join a labour party. The sewers have to work regularly overtime, because they need to fulfil their daily goals. These goals are being set so high, that it is not possible to fulfil them in the regular working time. The working time is 9-14 hours a day, which makes 80-100 hours a week. To work overtime is not an option; everyone who says that he/she doesn’t want to do extra hours loses his/her work. They have to work 6 or 7 days a week. The majority of the workers are mostly young women who need their job to contribute to their family’s livelihood. They are really frightened of losing their job. They accept the bad working conditions because they can be replaced every day by a new woman who is keen on this job. In the crowded city the work in the garment factories is the best job a young woman can get. When she loses it she needs to return home to her poor village and suffer even more from hunger. The payment of the workers isn’t based on transparent criteria. The payment depends on subjective criteria like beauty, age or interaction with the headmen. The date of payment is unregularly, often too late (middle till end of following month) and doesn’t match with the working hours they actually performed. Overtime isn’t paid transparently, too. The workers don’t have a contract of labour and don’t get an overview on their working hours and the resulting payment. 85% women are working at the factories. Women are paid worse than men. This is justified by saying that women do the “lighter” work than men. Women who restart to work in the factory after their pregnancy lose their former payment status and must take a newcomer wage. The women are suffering from the discrimination caused by the headmen. Sometimes they are discriminated, shouted or even hit. In cases of illness workers lose their jobs. There is no real health care system available. Health, hygiene and safety requirements are really bad. Drinking water is only available in one out of six factories. A factory canteen or day-care facilities for children are only in use when the auditor comes for a visit. Most of the workers do not have even heard about a code of conduct. But they were forced to say that everything is right in the factory when an inspection occurred. They were threatened with losing their jobs if they would tell the truth.<ref name="A" /> | The research study in 2008 revealed that the labour standards at Bangladeshi factories of the suppliers of KiK were very bad. The workers aren’t allowed to build up or join a labour party. The sewers have to work regularly overtime, because they need to fulfil their daily goals. These goals are being set so high, that it is not possible to fulfil them in the regular working time. The working time is 9-14 hours a day, which makes 80-100 hours a week. To work overtime is not an option; everyone who says that he/she doesn’t want to do extra hours loses his/her work. They have to work 6 or 7 days a week. The majority of the workers are mostly young women who need their job to contribute to their family’s livelihood. They are really frightened of losing their job. They accept the bad working conditions because they can be replaced every day by a new woman who is keen on this job. In the crowded city the work in the garment factories is the best job a young woman can get. When she loses it she needs to return home to her poor village and suffer even more from hunger. The payment of the workers isn’t based on transparent criteria. The payment depends on subjective criteria like beauty, age or interaction with the headmen. The date of payment is unregularly, often too late (middle till end of following month) and doesn’t match with the working hours they actually performed. Overtime isn’t paid transparently, too. The workers don’t have a contract of labour and don’t get an overview on their working hours and the resulting payment. 85% women are working at the factories. Women are paid worse than men. This is justified by saying that women do the “lighter” work than men. Women who restart to work in the factory after their pregnancy lose their former payment status and must take a newcomer wage. The women are suffering from the discrimination caused by the headmen. Sometimes they are discriminated, shouted or even hit. In cases of illness workers lose their jobs. There is no real health care system available. Health, hygiene and safety requirements are really bad. Drinking water is only available in one out of six factories. A factory canteen or day-care facilities for children are only in use when the auditor comes for a visit. Most of the workers do not have even heard about a code of conduct. But they were forced to say that everything is right in the factory when an inspection occurred. They were threatened with losing their jobs if they would tell the truth.<ref name="A" /> | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

Khorshed Alam is a leader of the Bangladeshi NGO “Alternative Movement for resources and Freedom” (AMRF). He summarised the inspections in his report for the “Clean Cloth Campaign” that take place as: “During these visits, the factory owners put on a show. Toilets are cleaned. The workers are forced to declare that there is no child labour in their factory, that the working atmosphere is good and that their wages are paid on time. They should also say that they are entitled to take regular holidays, are not forced to work overtime and do not have to work at night. When questioned about their pay, they should say they earn more than they actually do. Workers who are very young or look too young are forced to stay away from work when buyers or auditors visit. In the case of unannounced visits, they are locked in the toilets. There are known cases of workers presenting the real situation to buyers and consequently being dismissed for doing so.”<ref name="A" /> | Khorshed Alam is a leader of the Bangladeshi NGO “Alternative Movement for resources and Freedom” (AMRF). He summarised the inspections in his report for the “Clean Cloth Campaign” that take place as: “During these visits, the factory owners put on a show. Toilets are cleaned. The workers are forced to declare that there is no child labour in their factory, that the working atmosphere is good and that their wages are paid on time. They should also say that they are entitled to take regular holidays, are not forced to work overtime and do not have to work at night. When questioned about their pay, they should say they earn more than they actually do. Workers who are very young or look too young are forced to stay away from work when buyers or auditors visit. In the case of unannounced visits, they are locked in the toilets. There are known cases of workers presenting the real situation to buyers and consequently being dismissed for doing so.”<ref name="A" /> | ||

<br><br> | <br> | ||

=== <u>5) Summary and outlook</u> === | |||

This case study focuses on the globalisation issue in a concrete case. Globalisation leads to the opportunity to buy labour where ever you like for the cheapest price. Big discounter like the German garment discounter KiK use the new opportunities and let their garment products produced in Bangladesh. The Bangladeshi economy benefits from this but also falls in dependence because about 76% of their export-volume today is based on their textile industry. After the phase-out of the “Agreement on Textiles and Clothing” of the World Trade Organisation price-reductions take place to keep the client orders. The workers stand on the lowermost hierarchy level. They have to suffer directly from low prices and very short-term delivery promises. | |||

The installation of code of conduct systems like the one of the KiK company is theoretically a very good idea. I think that these conducts would really help to improve working conditions in developing countries if they would be implemented in reality. The problem of the code of conduct is its voluntary form. The described schedule for an unannounced audit sounds good, but it can be and really is undermined. The research study in 2008 by Khorshed Alam shows that voluntary conducts aren’t useful. He was interviewed by the journalist Christoph Lütgert („Panorama -- die Reporter" of the TV-channel ARD<ref>ARD-exklusiv: Die KiK-Story: http://www.ardmediathek.de/ard/servlet/content/3517136?documentId=5063630 (View: 28.2.2011).</ref>) again in 2010 and he affirms his former statement that little has changed since the code of conduct has been proclaimed. Audits were made, but only at “good” factories or with well-prepared workers that were forced to say all is really nice in the factory. Sometimes auditors are even tricked. | |||

I do support the idea of installation code of conducts but in my opinion it isn’t enough to delegate such inspections once or twice a year to an audit-team that visits some factories. I think a huge company like KiK should have a special and direct interest in social responsibility. They can actively do something for the workers at their supplier factories if they do stress in their contracts that they are willing to pay a higher, “fair” price if the supplier is willing to pay more wage to his workers and strictly follow the rules of the code of conduct. The payment and working conditions need to be controlled permanently by a changing group of KiK management members who stays directly in the Bangladeshi factory. In such a control system it is in fact impossible to present a “show” for one day. The everyday control will lead to the rise of a new feeling of security around the workers. The problem of corruption is avoided by a steadily rotation of controllers. In addition the discounter should conclude a long-term contract with its supplier, so that the job safety can be guaranteed.<br> <br>It would be really good if such big discounters like KiK with their market power decide to follow my propositions but I indeed take a very gloomy view of that. The consequence out of that must be the installation of governmental rules for worldwide trade and production. The government or worldwide organisations like the WTO, the EU or the USA should agree on strict rules for labour conditions and invent an independent powerful audition system. If the biggest industrial nations agree upon these rules of labour conditions they can link their import on the adherence of these rules. In this case the developing countries and their clients would have a direct stimulus to achieve the required aims because otherwise they cannot export or import anything. | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

=== <u>References</u><br> === | === <u>6) References</u><br> === | ||

<references /><br> | <references /><br> | ||

<br> --[[User:Reibe|Reibe]] | <br>--[[User:Reibe|Reibe]] 16:33, 28 February 2011 (CET) | ||

= <u></u>Literature review<br> = | = <u></u>Literature review<br> = | ||

Revision as of 16:33, 28 February 2011

Final version of the case study:

“The little Price” of the textile discounter KiK – consequences for labour conditions at textile factories in Bangladesh

1) Introduction

This case study wants to highlight a special part of the worldwide globalisation movement. The concentration lies thereby on the textile industry of low wage countries exemplified at the case of Bangladesh. Starting point for this study is the German garment discounter KiK and its price politics. To buy cheap clothes in Germany is something really normal for us today, but most of us do not consider or take care about where these clothes come from, by whom they are produced at which circumstances, for example labour conditions. This case study should offer a first inside-view into the economic methods that lead to such cheap prices and the humanity aspects considered with it.

At the beginning of chapter 2 I give a short presentation of Bangladeshi economy and the social situation. It is important to see labour conditions not only in comparison to Western standards but also to local living conditions based on real basic needs of economic survival. Globalisation as influential criteria on labour conditions is mentioned in the next paragraph. It will be shown that globalisation has had impact on Bangladeshi textile industry which was both positive as negative for the economy and the workers.

The chapter 3 is dedicated to the German garment discounter KIK and in general to the strategies huge discounter use to determine their prime costs. The profile of the KiK company will be presented and its advertising promises will get discussed. The market power of big discounter companies is the subject of the next paragraph. As an example the different price components of a T-shirt are shown. Additional aspects of the interaction of garment discounter and the textile industry at low wage countries are the purchasing practises of the business companies. Three tendencies can be made up that are of significant impact on the textile industry. As interesting last point in this chapter the KiK company statement on their behaviour as bulk buyer will be shown. This implies the code of conduct and how it is put into action and controlled.

After the previous chapter did present what a discounter does to achieve little prices and my introduction concerning Bangladesh as a place that offers cheap work, I like to focus on the Bangladeshi labour standards in detail in this chapter 4. A research study gives concrete inside views on insufficient labour conditions in garment factories which produce cheap clothes for the Western market, also for the KIK company in Germany.

The missing labour conditions lead me to the next and last chapter 5. It is dedicated to a final summary and an outlook. In this chapter I want to discuss the usefulness of the code of conduct in general and in this example. During a final outlook I like to present some possible strategies for the future for example more powerful conducts and under which political circumstances they can get active.

2) Bangladesh – economic and social facts

2.1 Geographic and social information

In Bangladesh lives a population of about 164,4[1] million people on an area of 147.570 square kilometers. That makes the country to “one of the most crowded on Earth”[2]. Bangladesh lies in the Ganges-Brahmaputra river system which makes the land very fructuous. The annual floods on the one hand are helping and welcomed because they give fertility to the land, but on the other hand they sometimes destroy the harvest and kill the people who are living near the river. Most of the Bangladeshi people live from agricultural production, for example “wheat, barley, maize, potatoes, pulses, bananas and mangoes”[3]. The Bangladeshi people are very poor. Around 25% of the population is suffering from hunger. The garment industry contributes enormously to the economic development. 2 million people are working at the 3.500 factories. 85% of them are women from the rural regions who need to work in the cities because of job shortage in their home regions. The work at the garment factories is their only chance to receive income that helps to save the survival of the family.[3]

2.2 The Bangladeshi garment and textile industry

The “Agreement on Textiles and Clothing” of the World Trade Organisation (ATC) in 1995 was designed to avoid the massive export of clothes produced in emerging and developing countries to industrial countries.[4] The ATC restricted the imports of textiles and clothing through quotas. Huge garment producers and exporters like China, India or Hong Kong were affected by these quotas. Bangladesh was not affected, because it was a very poor developing country and therefore took its chance and established a growing textile industry. The exports of clothes rose from 600 million US dollars in 1990 to about eight billion US dollars in 2006.[3] The export products of Bangladesh shifted from raw material, like jute, and jute products (90%) to clothes based on cotton. “The textile and clothing industry now accounts for 76% of the total export volume of Bangladesh.”[3] Fishery (7%) and the raw material jute (5%) are the two other important export-products of Bangladesh. The Bangladeshi economy today is very strong orientated on the textile industry. That may cause problems if the export declines and of cause if the needed raw material for clothing cotton gets expensive. Cotton is not cultivated in Bangladesh itself therefore it must be imported before it can be part of the garment production. As the “Agreement on Textiles and Clothing” phased out in 2005, many experts were afraid of a possible collapse of the Bangladeshi textile industry because they now had to compete against China and India for gaining orders. Bangladesh has managed to sustain their contract partners from the EU and USA because the production at Bangladesh is possible at an “extremely low wage level”.[3]

3) The discounter KiK and its methods

3.1 Profile of the garment discounter KiK

The KiK company was founded in 1994 by Stefan Heinig and the Tengelmann group. KiK is an abbreviation for the German slogan “der Kunde ist König”, that means “the customer is the king”. The mission statement of KiK is that everyone can get completely dressed from stockings to the cap for only 30 Euro. KiK is a quickly growing textile discounter. Today the KiK company consists out of 3.000 stores in Germany, Austria, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Hungary and Slovakia. Each year about 200 new stores are opened. The annual turnover is more than one billion Euros. KiK is the largest textile discounter in Germany. The rage of products includes on one side ladies, men, children and baby wear and on the other side giftware, toys, accessories, home textiles, underwear and stockings. KiK uses the known German TV-starlet Verona Pooth for advertising their products as a testimonial. The KiK company stresses that they offer good quality for a very cheap price. The quality is tested by the quality assurance management of KiK. In Addition KiK works together with the international testing institute SGS Fresenius and the TÜV institute Rheinland. On the KiK homepage customers can watch a short film that shows the quality management.[5][6][7]

3.2 Market power of discounters

3.2.1 How discounter determine the prices

Why can discounter sell their products for such little prices? As you can read on the KiK homepage their basis business model is to order a big number of pieces from each product and deliver them with an intelligent logistic system to their stores. It is important to plan an attractive product-range and be flexible enough to order quickly new products when they have sold-out.[6] The production of demanded clothes needs to be a “Just-in-Time” production, because this system allows a maximum of flexibility and very little costs for storage.[8]

The big volume orders have both advantages and disadvantages for the textile producers at Bangladesh. As an advantage you can name that the factories are working to full capacity. This is under the economic point of view a status that one should aspire. The workers have jobs and are paid. The problem is that such factories depend on only one huge client. If this client decides to search for a new producer the whole factory is without an order. That means the machines stand still and the workers are dismissed. The factory owner won’t have enough money to pay his bills like rental fee or electricity costs. If he doesn’t get a new order he will soon be bankrupt. So, the dependence to one client is a clear disadvantage for the producers. The big client uses his power to keep the prices down. “The largest discounters pay their suppliers up to 15-20 percent less for their goods than normal department stores (ActionAid, 2007, p. 16).”[3] The consequence of steadily decreasing prices is the decreasing of the already low wages of the garment workers.

In chapter 2 I have already mentioned the “Agreement on Textiles and Clothing” (ATC) of the World Trade Organisation that phased out in 2005. After this phase-out a hard competition between Bangladesh and the former restricted countries like China and India began with the consequence for Bangladesh – which is very depending on export of clothing – that price reductions started which were to be paid by the garment workers in the end. “The poor countries, competing to retain their clothing industry, try to offer the lowest wages.”[3]

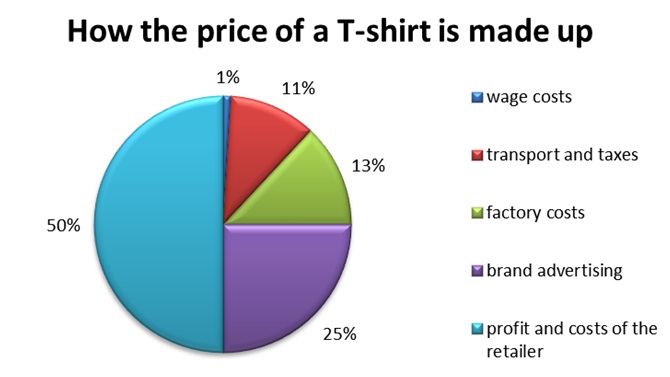

Figure 1 is adapted from the brochure of the “Clean Clothes Campaign”. It is necessary now to give a short presentation of the “Clean Clothes Campaign” because it offers important information in its brochure that is used as one of the key literature in this case study. The key aim of the “Clean Clothes Campaign” is to improve the working conditions in the global garment industry, especially in less developed countries. This campaign is widely supported by many NGOs and labour unions.[9] The figure shows of which price components a T-shirt price is made up. “Wages only account for 0.5-1 percent of the ultimate selling price of the product”.[3] The large portion of the price is gained outside Bangladesh in Western industrial nations like Germany. Only the factory and wage costs remain in the Bangladeshi economy. A huge amount of the later price is spend for marketing activities and the rest, about 50 percent is used to cover costs of the retailer and to gain some profit.[3]

This figure 1 is adapted from the brochure of the “Clean Clothes Campaign”.[3]

To make it easier to understand I like to give a concrete example. If we think about 1% wage costs for a normal T-shirt that is sold to us for 20 Euro, only 20 Cent of the price belongs to wage costs. I think this is remarkable information, because it should be easy to increase the wages without any massive price explosions. I even risk saying that nobody of the customers would recognize the effect of raised wages. The problem is that the discounters only think in large scales. If they want to launch an order to a factory owner in Bangladesh they compare the complete price for their order. It is a highly competitive process in which only the quickest and cheapest supplier wins. How the factory owner manages to produce the ordered amount of clothes is not important for the discounter. This lies in the responsibility of the Bangladeshi factory owner. He himself also wants to gain profit and therefore reduces his costs, especially the wages of his workers. It is all a downward spiral to satisfy the dictated low prices of the huge discounters.

3.2.2 Three tendencies in purchasing practise

The big discounters who have a huge market power use three main purchasing practises in their direct interaction with their suppliers from developing countries. These three tendencies are receiving their products “cheaper” and “quicker” and in addition are including the reduction of their own risk by applying “risk-shifting” methods.

As said in the previous paragraph, prices are dictated. The producer in Bangladesh takes such small prices because otherwise he loses his order. Gisela Burkhardt, an expert for development politics, confirms that “suppliers are threatened with being removed from the lists, if they do not reduce the price.”[3] Although the costs of energy have risen, the prices for garment still decline. This is again only possible because the wage costs are reduced.

The second practise method is the timely pressure that is put on the suppliers. The discounter demands quick production time. There are two main causes to name for this demand. On the one hand the fashion business today is changing very quickly. Collections in the past change only twice a year, but today there can be changes every month, that mean twelve times a year.[3] The discounter wants to be very flexible which implies that their store-houses should act only like a logistic-centre where in-coming products are reorganised and immediately delivered to the final stores. So at best case nothing stays long in the store-houses. This system is in fact very economic but needs a good working, dependable and especially quick supply chain. Today the internet offers the possibilities to launch an order for products that are produced on the other side of the world. Again the producers are under pressure to react quicker than their competitors. They do not have enough time to calculate thoroughly. They depend on the orders and therefore no order is much worse than a bad order for a low price.

The last point is the risk-shifting procedure. It goes along with the need to be able to produce “Just-in-Time” when a powerful discounter launches an order. The owner of a factory in Bangladesh needs to purchase the materials, like yarn, buttons, zips and cloth for the production on his own risk before he gets a new order. The delivery times have shorted massively. A received order on Sunday has to get delivered by Wednesday.[3] “The company not only saves storage capacity, but also passes on all risks to the suppliers.”[3] The need to store materials for a future production which isn’t yet saved by a contract leads again to an enlargement of the dependency of the Bangladeshi supplier on the big discounter.

3.3 “Code of Conduct” by KiK – What does KiK to guarantee labour standards?

Stefan Heinig, the CEO of KiK, points out: “At KiK, the social, ecological and economic added value is very important. This is why today, we take advantage of our strength and size to campaign for the principles of sustainability and to promote continuous improvement. In 2006, we established a strict code of conduct to which all our suppliers are committed. We consequently work on the implementation of the entailed demands. Even though it needs a lot of effort, patience and the ability to take occasional setbacks, our measures in regards to social responsibility serve as role models in the discount domain and help to impose standards.”[10]

This statement is very important because KiK sets his own levelling board they must achieve or otherwise can get criticised for. As a next step it is necessary to take a closer look to the established code of conduct by KiK in 2006. The code of conduct describes social standards for all trading partners of KiK, including those in Bangladesh and China. “The regulations of the code of conduct contain all the usual conventions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) for good working conditions. These include adhering to maximum working hours and paying a minimum wage as well as a safe and clean working environment, freedom of assembly and collective bargaining and the prohibition of child labour.”[10]

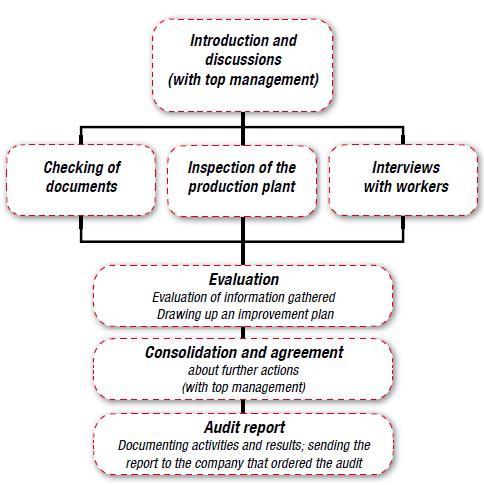

The adherence of the code of conduct rules is controlled systematically by inspections that are carried out by independent audit organisations. These social audits do follow a schedule plan that is showed in figure 2.

Figure 2: Schedule of a social audit at supplier factories in Bangladesh and China.[10]

The auditor arrives at the factory unannounced and starts his audit by talking to the management and asking for some documents. Then he inspects the whole factory with regard of working conditions, safety aspects and health requirements. He also chooses workers for a later interview. This interview is carried out in absence of the authorities of the factory.[10] “This means that they can find out whether the maximum working hours are adhered to and whether their monthly wages, including overtime, are paid correctly.”[10] After this the auditor evaluates the factory and talks to the management about lacking standards and a suitable procedure to reach the conduct wished state. The audit report is send to the KiK home-office. After a while a re-audit takes place where all criticised points are under examination again.

This last paragraph describes the way an audit should be and if it functions this way, it is definitely a good instrument to control the code of conduct. The next chapter is based on a research study in 2008 conducted by the society of “Alternative Movement for resources and Freedom” (AMRF), a Bangladeshi NGO, by order of the “Clean Clothes Campaign”. This study was made to reveal the real working conditions in the factories of the suppliers of KiK and Lidl. A team of researchers interviewed 136 workers in six factories. They answered questionnaires and 31 of them were asked in group discussions.[3] Chapter 4 will present the opposite perspective to the announcement of KiK. It shows how the rules and control-audits are tricked and under which conditions the mostly female workers suffer.

4) Bangladeshi labour standards in supplier-factories of KiK

The research study in 2008 revealed that the labour standards at Bangladeshi factories of the suppliers of KiK were very bad. The workers aren’t allowed to build up or join a labour party. The sewers have to work regularly overtime, because they need to fulfil their daily goals. These goals are being set so high, that it is not possible to fulfil them in the regular working time. The working time is 9-14 hours a day, which makes 80-100 hours a week. To work overtime is not an option; everyone who says that he/she doesn’t want to do extra hours loses his/her work. They have to work 6 or 7 days a week. The majority of the workers are mostly young women who need their job to contribute to their family’s livelihood. They are really frightened of losing their job. They accept the bad working conditions because they can be replaced every day by a new woman who is keen on this job. In the crowded city the work in the garment factories is the best job a young woman can get. When she loses it she needs to return home to her poor village and suffer even more from hunger. The payment of the workers isn’t based on transparent criteria. The payment depends on subjective criteria like beauty, age or interaction with the headmen. The date of payment is unregularly, often too late (middle till end of following month) and doesn’t match with the working hours they actually performed. Overtime isn’t paid transparently, too. The workers don’t have a contract of labour and don’t get an overview on their working hours and the resulting payment. 85% women are working at the factories. Women are paid worse than men. This is justified by saying that women do the “lighter” work than men. Women who restart to work in the factory after their pregnancy lose their former payment status and must take a newcomer wage. The women are suffering from the discrimination caused by the headmen. Sometimes they are discriminated, shouted or even hit. In cases of illness workers lose their jobs. There is no real health care system available. Health, hygiene and safety requirements are really bad. Drinking water is only available in one out of six factories. A factory canteen or day-care facilities for children are only in use when the auditor comes for a visit. Most of the workers do not have even heard about a code of conduct. But they were forced to say that everything is right in the factory when an inspection occurred. They were threatened with losing their jobs if they would tell the truth.[3]

Khorshed Alam is a leader of the Bangladeshi NGO “Alternative Movement for resources and Freedom” (AMRF). He summarised the inspections in his report for the “Clean Cloth Campaign” that take place as: “During these visits, the factory owners put on a show. Toilets are cleaned. The workers are forced to declare that there is no child labour in their factory, that the working atmosphere is good and that their wages are paid on time. They should also say that they are entitled to take regular holidays, are not forced to work overtime and do not have to work at night. When questioned about their pay, they should say they earn more than they actually do. Workers who are very young or look too young are forced to stay away from work when buyers or auditors visit. In the case of unannounced visits, they are locked in the toilets. There are known cases of workers presenting the real situation to buyers and consequently being dismissed for doing so.”[3]

5) Summary and outlook

This case study focuses on the globalisation issue in a concrete case. Globalisation leads to the opportunity to buy labour where ever you like for the cheapest price. Big discounter like the German garment discounter KiK use the new opportunities and let their garment products produced in Bangladesh. The Bangladeshi economy benefits from this but also falls in dependence because about 76% of their export-volume today is based on their textile industry. After the phase-out of the “Agreement on Textiles and Clothing” of the World Trade Organisation price-reductions take place to keep the client orders. The workers stand on the lowermost hierarchy level. They have to suffer directly from low prices and very short-term delivery promises.

The installation of code of conduct systems like the one of the KiK company is theoretically a very good idea. I think that these conducts would really help to improve working conditions in developing countries if they would be implemented in reality. The problem of the code of conduct is its voluntary form. The described schedule for an unannounced audit sounds good, but it can be and really is undermined. The research study in 2008 by Khorshed Alam shows that voluntary conducts aren’t useful. He was interviewed by the journalist Christoph Lütgert („Panorama -- die Reporter" of the TV-channel ARD[11]) again in 2010 and he affirms his former statement that little has changed since the code of conduct has been proclaimed. Audits were made, but only at “good” factories or with well-prepared workers that were forced to say all is really nice in the factory. Sometimes auditors are even tricked.

I do support the idea of installation code of conducts but in my opinion it isn’t enough to delegate such inspections once or twice a year to an audit-team that visits some factories. I think a huge company like KiK should have a special and direct interest in social responsibility. They can actively do something for the workers at their supplier factories if they do stress in their contracts that they are willing to pay a higher, “fair” price if the supplier is willing to pay more wage to his workers and strictly follow the rules of the code of conduct. The payment and working conditions need to be controlled permanently by a changing group of KiK management members who stays directly in the Bangladeshi factory. In such a control system it is in fact impossible to present a “show” for one day. The everyday control will lead to the rise of a new feeling of security around the workers. The problem of corruption is avoided by a steadily rotation of controllers. In addition the discounter should conclude a long-term contract with its supplier, so that the job safety can be guaranteed.

It would be really good if such big discounters like KiK with their market power decide to follow my propositions but I indeed take a very gloomy view of that. The consequence out of that must be the installation of governmental rules for worldwide trade and production. The government or worldwide organisations like the WTO, the EU or the USA should agree on strict rules for labour conditions and invent an independent powerful audition system. If the biggest industrial nations agree upon these rules of labour conditions they can link their import on the adherence of these rules. In this case the developing countries and their clients would have a direct stimulus to achieve the required aims because otherwise they cannot export or import anything.

6) References

- ↑ Report about human population 2010. http://www.weltbevoelkerung.de/pdf/dsw_datenreport_10.pdf (View: 25.2.2011).

- ↑ Geographic information about Bangladesh. http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/travel/countries/bangladesh-facts/ (View: 25.2.2011).

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 Brochure of Clean Clothes Campaign: Who pays for our clothing from Lidl and KIK? Published at Kampagne für Saubere-Kleidung (Clean Clothes Campaign; CCC). Published as brochure at January 1st, 2008: http://www.saubere-kleidung.de/downloads/publikationen/2008-01_Brosch-Lidl-KiK_en.pdf

- ↑ Globalisierung. Author: PD Dr. Norman Backhaus. Published by Prof. Dr. Rainer Duttmann, Prof. Dr. Rainer Glawion, Prof. Herbert Popp, Prof. Dr. Rita Schneider-Sliwa. Published in Westermann Bildungshaus Schulbuchverlage, Braunschweig 2009, page 171.

- ↑ Data and facts abour KiK: http://www.kik-textilien.com/fileadmin/Abteilungen/Kommunikation/Presse/Zahlen-Daten-Fakten-KiK_2011.pdf (View: 26.2.2011).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 KiK - company profile: http://www.kik-textilien.com/unternehmen/presse/pressearchiv/unternehmensprofil/pm-unternehmesportait/ (View: 26.2.2011).

- ↑ KiK company film: http://www.kik-textilien.com/unternehmen/presse/pressearchiv/unternehmensfilm/ (View: 26.2.2011).

- ↑ Globalisierung. Author: PD Dr. Norman Backhaus. Published by Prof. Dr. Rainer Duttmann, Prof. Dr. Rainer Glawion, Prof. Herbert Popp, Prof. Dr. Rita Schneider-Sliwa. Published in Westermann Bildungshaus Schulbuchverlage, Braunschweig 2009, page 167.

- ↑ Profile of Clean Clothes Campaign: http://www.saubere-kleidung.de/ccc-60_wir/ccc-60_wir-ueberblick.html (View: 28.2.2011).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Published in CSR brochure of KIK, October 2010. Available from: http://www.kik-textilien.com/uploads/media/CSR-Broschuere_eng.pdf (View: 26.2.2011).

- ↑ ARD-exklusiv: Die KiK-Story: http://www.ardmediathek.de/ard/servlet/content/3517136?documentId=5063630 (View: 28.2.2011).

--Reibe 16:33, 28 February 2011 (CET)

Literature review

Resource 1:

Title: Internationale Arbeitsstandards in einer globalisierten Welt. Published by Ellen Ehmke, Michael Fichter, Nils Simon, Bodo Zeuner (Hrsg.). Published in VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / GWV Fachverlage GmbH, Wiesbaden 2009.

a) Content of the resource

This book is based on and developed during a project module about International Labour Standards (ILS) in a globalised world at the Otto-Suhr-Institute for politics at the University of Berlin 2005 until 2006. The texts were written by students of this course and their professors. It is an overview about the problem of International Labour Standards (ILS).

b) Usefulness of the resource

This book offers 4 main chapters in which different sub-texts are located. The first chapter gives an introduction and shows a theoretical placement. This chapter is interesting for me because I get an overview of the interaction and the consequences of globalisation and labour standards in deveolping countries. The "race to the bottom theory" is of special interest for me. The second chapter introduces actors and organisations of ILS. The third chapter highlights instruments of ILS. In this part two articles are especially interesting. The first gives a concrete example in the textile industry: the code of conduct by Hennes & Mauritz. The second article appeals to the question "why" the compliance with core labour standards is so low in developing countries. Chapter four ends with an outlook and shows some perspectives.To sum up: This book provides information on ILS and some general aspects on globalisation and its consequences on labour conditions in developing countries. I think it is very useful.

c) Limitations of the resource

It doesn't offer information on the special case I like to highlight as an example in my case study. I like to present the German KIK company as an example for the textile industry that uses globalisation for obtaining cheap manpower.

Resource 2:

Title: Globalisierung. Author: PD Dr. Norman Backhaus. Published by Prof. Dr. Rainer Duttmann, Prof. Dr. Rainer Glawion, Prof. Herbert Popp, Prof. Dr. Rita Schneider-Sliwa. Published in Westermann Bildungshaus Schulbuchverlage, Braunschweig 2009.

a) Content of the resource

This book provides a general overview on globalisation issues. It catagorizes globalisation and gives a historical background to the development of globalisation. The book offers a chapter on the field of economy.

b) Usefulness of the resource

For me this book is of interest because it offers me on the one side an overview and introduction on globalisation, so that I can get in touch with the theme, and on the other side it provides a description of the production-development in the textile industry.

c) Limitations of the resource

It doesn't offer so many concrete examples. It is more kind of an overview.

Resource 3:

Title: Die KIK-Story - die miesen Methoden des Textildiscounters. Published in TV at „Panorama -- die Reporter" ARD. Author: journalist Christoph Lütgert. The video was first broadcasted at August 4th, 2010: http://daserste.ndr.de/ndrsondersendungen/ard1584.html

In addition: Online newspaper article: Das schäbige Geschäft der Preisdrücker (TV-Film über Textildicounter KIK). Published at Spiegel Online. Author: Christian Teevs. Published at August 4th, 2010: http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/tv/0,1518,709922,00.html

a) Content of the resource

This video shows the methods of the German textile discounter KIK to reduce their costs. The sufferer are the German sales people and especially the worker of the textile facility in Bangladesh. The sewer were interviewed about their labour conditions. The Bangladeshi sewer earn only 25 Euro per month and have barely enough money to buy food.

b) Usefulness of the resource

These two resources are very useful. They are the starting point of my case study. They provide a special case that I like to focus on. The theme is based on these resources, the labour standards in the textile industry focused on especially Bangladesh. The video offers an insight view in the textile facilities and the living conditions of sewer in Bangladesh. Khorshed Alam, a researcher on labour standards, is also interviewed and bemoans that KIK hasn't changed labour conditions even though there has been lot of criticism in the last years.

c) Limitations of the resource

This reportage only views some aspects of labour conditions. It is necessary to see it as a starting point and investigate more resources connected with ILS.

Resource 4:

Title: Textilarbeiter in Bangladesch wollen höhere Löhne. (Protest gegen Ausbeutung). Published at Spiegel Online. Author: Christian Teevs. Published at Juli 30th, 2010: http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/0,1518,709358,00.html

a) Content of the resource

This online newspaper article informs about the demonstrations of worker and sewer in Bangladesh. They demonstrate in Dhaka for higher minimum wages. Bangladesh has the lowest industrial wages worldwide. It was about 19 Euro and is now raised to 34 Euro. That isn't enough for the worker. They say that the government acts the way the textile industry desires to.

b) Usefulness of the resource

It shows another side of the labour standard problem and how the exploited people start to engage for their needs. It gives me additional points for new investigation. What are the wishes of the textile working labour union?

c) Limitations of the resource

This article is very short but leads me to investigation about special aspects of labour standards. I also read in another article that says that often the buildings of the facilities are not quite safe. Fire and collapses of buildings occured in the past. During such catastrophes many workers died.

Resource 5:

Title: Who pays for our clothing from Lidl and KIK? Published at Kampagne für Saubere-Kleidung (Clean Clothes Campaign; CCC). Published as brochure at January 1st, 2008: http://www.saubere-kleidung.de/downloads/publikationen/2008-01_Brosch-Lidl-KiK_en.pdf

In addition the online article: http://www.saubere-kleidung.de/2008/ccc_08-01-30_pu_discounter_lidl-kik.html

a) Content of the resource

This brochure offers a lot of information about the textile industry in Bangladesh and the methods of the textile discounter KIK.

b) Usefulness of the resource

It is very useful for my case study. There are articles included of the expert for labour standards in Bangladesh Khorshed Alam. These detailed descriptions support me with the key information I need for developing my case study. The campaign is launched by activists who are really engaged in the issue of labour standards and know about globalisation influences. They highlight many important points.

c) Limitations of the resource

The study for the campaign was published in 2008 and is therefore 2 years old. But I think that this doesn't matter much, because the other articles I read support my opinion that unfortunately nothing has really changed since 2008.